- War: If a Western country is involved in a war (or an ally - as in the case of Saudi Arabia in Yemen) then they are routinely assigned the entire responsibility for that war, including for all the terrible things done by those they are fighting.

- Illiberalism: Government oppression of religious and sexual minorities, political opposition, free press, and so on is routinely attributed to 'colonial era laws' or continuing Western ideological influence.

- Misgovernance: Government dysfunction and corruption are routinely blamed on Western consumers/companies' demand for natural resources; terrible environmental and labour regulations (or enforcement) are likewise blamed on Western demand for cheaper products

Unfortunately, many such efforts appear to be merely performances of open-mindedness. It is particularly discouraging to see promoters of decolonisation systematically neglecting the intellectual agency of people outside the West. An example of this in my own field of philosophy is the valorisation of 'authentic' African philosophy, identified as intellectual traditions untainted by corrupting European intellectual influences. This authenticity movement has spent decades trying to establish a 2-tier intellectual system in which Western (i.e. real) philosophers are understood to have a moral and intellectual duty to try to escape their cultural filter bubble while non-Western intellectuals can only count as intellectuals so long as they stay within their filter bubbles (see further Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò). When this is conjoined to the idea that people of African heritage should study their own African philosophy rather than 'white' philosophy one gets a racial hierarchy of the intellectual sphere that 19th century white supremacists would have found disturbingly congenial.

I will probably try to write something properly about that sometime. Today I want to get into a related failure of decolonisation: that the moral agency of non-Western actors is still not taken seriously. Time and again we see their actions analysed in the news, politics, and even academic forums as if they were merely caused rather than reasoned, objects rather than subjects like us. Let's start with some examples to illustrate the problem.

1. Wars

Whenever there is a war in which a Western country (or ally) is involved, the war is routinely assumed to be the responsibility of the Western country. Since wars create suffering, that means the Western country is assumed to be responsible for all the suffering. For example, it was routine to see all the civilian deaths taking place in Iraq and Afghanistan being attributed to the US military, even though the great majority were directly or indirectly caused by the terroristic insurgencies the US military was fighting. I think this was because many people looking at those wars could only perceive one moral agent - the USA - and so could only find one actor liable for moral reactions like blame.

The obvious consequence of this is that the non-Western actors involved are not held morally accountable for their own appalling choice to wage sectarian and terroristic insurgencies against civilian populations. This lack of scrutiny also leads their claims to be representing 'the people' - rather than a particular power-hungry faction - are often taken at face value.

But there are also further consequences. In particular, the asymmetrical attribution of moral agency makes these wars seem one-sided - as if all the shooting and bombing and suffering were being imposed by the US government on the people of Afghanistan and Iraq just because it enjoys doing that kind of thing. But wars are fought between political actors over the fundamental question 'Who should be in charge here?' The seemingly forever wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were a result of the US military trying strenuously to prevent terroristic insurgencies with minimal public support from imposing brutal theocratic/sectarian tyranny on tens of millions of people. Those who campaigned for an end to the wars were campaigning for America to let very bad guys win - i.e. exactly what happened when America finally left Afghanistan and 40 million people were abandoned to the tender mercies of a bunch of violent fundamentalist nutjobs unrepresentative of the values and identity of the society they now get to rule.

So neglecting the moral agency of non-Western political actors leads directly to a neglect of non-Western people's rights and interests. Wars are struggles between political actors about significant political questions - involving rights and power and justice. If we only allow ourselves to see one side in a war as a moral agent then we cannot see what the struggle is about, what the stakes are and where justice lies.

Even worse, in cases where wars cannot be tied to some Western actor or other, we often don't see them at all. Just think about how easily wars like Armenia vs Azerbaijan or the ongoing civil wars in S. Sudan, Ethiopia, and CAR slip out of the news and our political system's attention. The implicit reasoning seems to be as follows:

- Only Western actors have the power to cause significant events to happen in the world

- If a war is a significant event then it must be caused by a Western actor

- This war doesn't seem to be caused by a Western actor

- Therefore, this war isn't significant

2. Illiberal Values

In the 2010s a 'kill the gays' law was extensively trailed by Ugandan pro-government politicians (though never quite passed). The response to this in the West was I think typical of the phenomenon I am talking about.

- Some commentators (e.g. Peter Tatchell) argued that homosexuality had been widely accepted in Africa until the European colonialists arrived with their homophobic Christian based bigotry and passed laws against it. Apparently, Western actors have so much more moral agency than non-Westerners that they are still controlling events 50 years after they are gone. Also, apparently, Africans have authentic values that have been hidden from them by colonialism and which they have to be told about by Western activists.

- Other commentators (such as John Oliver) argued that a small group of American evangelicals had brought about the new law by successfully persuading Ugandan politicians and the wider public of their bigoted view of Christian morality. Apparently, Ugandans are an incredibly credulous people who will believe any bullshit peddled by Western ideologues - no matter how crazy or hateful, or how unsuccessful the same ideologues were at persuading their fellow Westerners.

Here is a rather more plausible scenario. President Museveni was becoming more and more clearly a dictator as he was forced to shift from the pseudo-democracy of managed elections to the nakedly violent suppression of dissent. He needed to distract his citizenry from the violation of their constitution. Some evangelical twits visited and got on TV. Museveni saw the idea had some popular traction and went with it. After all, what better way to help people transition from citizens to mere subjects than to hand them a group whose dignity has been reduced even further, and over whom they can exercise their own despotism. This is still a sad story and still shows Uganda in a pretty bad light. But it is at least Uganda's own story.

3. Misgovernance

Most non-Western governments do not run things well, and their people suffer greatly as a result of entirely avoidable problems, from lack of utilities to appalling public services like health care, education, and policing. Yet again, Western observers analyse this in a way that excuses the people in power from responsibility for the decisions they make.

For example, that children are mining coltan by hand in the Congo is supposedly explained by the greed of Western companies and consumers looking to get the lowest price rather than the vile kleptocrats (and neighbouring opportunists like Kagame and Museveni) who run the country entirely as an extractive enterprise. How exactly such inefficient methods of production are supposed to save us money, and who would care anyway about a few pennies when buying a thousand dollar i-phone is never made clear. But if you continue asking questions you will be told about the terrible things that Belgium did to its colony and the CIA's nefarious plot against an apparently promising independence leader, Patrice Lumumba, 60 years ago. To be clear, I am not saying that Western actors (historical and contemporary) bear no responsibility for how things go in the Congo. I am saying that we seem systematically unable to even consider the responsibility of non-Western actors and that this is manifestly absurd.

Let's take another, more specific example. In 2013 an 8 storey building in Dhaka collapsed killing over 1,000 people (Rana Plaza). The building contained several factories which manufactured clothing for various Western retailers including Benetton, Primark, and Walmart. After the catastrophe, newspapers, labour unions, and opposition political parties in Bangladesh blamed greedy law-dodging companies and the government's lax building standards and enforcement and demanded accountability and for the identification of other buildings at risk. But most Western commentators blamed the Western companies like Primark, whose only connection to the tragedy was that they bought clothes made by companies based there.

Firstly, it seems bizarre to assign moral responsibility for this disaster to private foreign companies so far removed from the decisions that caused the disaster. Secondly, this was accompanied by a powerful call for these Western clothing retailers to fix the problem of lax building safety codes and enforcement in Bangladesh (which some of them even tried to do). There was a failure to even consider that the most relevant moral agent in the case of laws and their enforcement might be the Bangladeshi government. Why? There seems to be an implication here that we don't bother to blame non-Western actors because we assume they won't be responsive to moral criticism, while Western actors will be. But this is another way of saying that non-Western actors are not really moral agents.

Once again, there seems to be an asymmetry. When such disasters happen in Western countries there is immediately strenuous complaint about the government's failings and demands for accountability and improvements (e.g. the reaction to the Grenfell Tower fire). But when non-Western governments fail their people, we do not seem to take them seriously enough to even bother to complain. The implication is that we do not believe that non-Western peoples deserve a functioning competent government to secure their rights and interests - some cobbled together supply chain management system run by a coalition of Western companies is fine. If this is not a colonialist attitude, it seems very close.

What Counts as the West?

I am pretty confident that there is a pervasive pattern here in the way political actors are perceived, but I admit it is a bit more complicated than I have so far presented it.

First, I say that this is a pervasive pattern but of course it is a pattern rather than a rule. There are exceptions and ambiguous cases and also spectrum of variation that may be correlated with the political orientation of the media you consume. For example, I find that more leftist commentators and media tend to downplay non-Western moral agency more than rightist ones. I think what may be going on there is that the left has particular intellectual instincts to downplay agency in favour of structure, and to moralise material inequality as prima facie evidence of oppression by the richer/stronger party over a weaker victim.

Second, the bias I am analysing doesn't affect all international analysis equally. It certainly seems to dominate the low level analysis enjoyed by people who like to have their beliefs echoed back to them (i.e. most news media and punditry). However, I wouldn't expect it to be as significant among analysists working for professional organisations with an interest in making the right calls rather than in getting more pageviews, such as research institutes and government agencies. Thus, ironically enough, Western governments may be far less prone to this 'colonial' attitude than their general publics, and far more appreciative of how difficult it actually is to get good things done beyond their borders. Nevertheless, public opinion exerts a powerful sway on the common sense of the people entering government, and also sets constraints and goals that governments are expected to meet.

Third, what I have been calling the West doesn't refer to the traditional West as defined in e.g. critical race theory as the 'white' former colonialist powers. In fact I don't think we need a racialist hierarchy thesis at all to understand and explain this phenomenon (although racial stereotypes may still play a role). For example, mainstream analysis has no problem recognising non-white actors as moral agents, including enemies of 'the West' such as Al Qaida, ISIS, and the rulers of Russia, Iran, and China, as well as allies like Saudi Arabia. What these have in common is that they are perceived as powerful on the world stage. In contrast, the countries where moral agency is most completely ignored tend to be much smaller and poorer (such as in sub-Saharan Africa, central America, and S.E. Asia).

In other words, what I think what may be driving this what might better be called 'neo-colonial' attitude is not commentators' racism but their conflation of the pitiful global agency of a country with the powers and responsibilities of the political actors within that country. We are making the narcistic mistake of evaluating people's influence by the influence they could have on us. This is a significant error because the fact that a dictator or rebel leader couldn't muster much firepower or spending power or influence on international institutions compared to the USA or even Coca Cola is pretty much irrelevant to whether they can do awful things to the many poor people who are under their power.

Moreover this misperception of global power asymmetries generates a faulty analysis of moral agency. The less powerful we perceive a country to be, the less seriously we take those who rule them and so the less seriously we take their behaviour. If they are less powerful than us then their decisions can't matter as much as ours. So when they do awful things it must be Western actors who are really responsible for what happened because our superiority supposedly allows us meta-control over the rules of game that they are trying to play. This resembles the way we hold parents responsible for the destructive misbehaviour of toddlers, i.e. it is massively patronising.

It is also quite inaccurate since it vastly overestimates Western actors' power and underestimates non-Westerners'. Recall that the most powerful country in the world spent 20 years, $2 trillion, and massive bureaucratic resources dismally failing to change the rules of the game to Western style constitutional democracy in one of the objectively weakest and poorest countries in the world. Indeed, a common outcome of this approach is to hold Western actors responsible for things they have little or no control over; while non-Western actors making significant and morally awful decisions escape blame entirely.

There are still further consequences of the moral asymmetry assumption. I will conclude by considering two.

Intellectual Laziness

The 'blame everything on the West' approach encourages extraordinary intellectual laziness and complacency about how the world works. To explain any bad event, all you need to do is:

- Search to see whether the names of Western countries or key words like 'CIA' or 'Western multinational' can be associated with it

- Stop your research as soon as you find one.

- You have now proved what you set out to believe.

By this simple method even the worst crimes - even genocides - can be blamed on Western actors rather than the people right there planning and leading them. The Rwanda genocide for example is routinely blamed on Belgian colonial practises and US/French reluctance to support military intervention to stop it.

Or take the mass murder of 500,000 to 1.2 million 'communists' in Indonesia in 1965-6. Now it might seem that this is easily explained as part of a coup by the Indonesian general Suharto. Suharto after all was in control of the military, which organised and carried out most of the massacres. He also had an obvious political motive for wanting to destroy the communist party power base of the civilian government that he was trying to replace. But all this is invisible to those who take the 'only Western actors can be moral agents' view of the world.

To those people non-western actors are just interchangeable puppets whose strings are pulled by the prime movers. They search and find references to Western governments' antipathy to the previous regime's communist sympathies and to specific actions demonstrating support for and even complicity in the killings (namely, providing communications equipment, small arms, and lists of names - none of which seem like things the Indonesian armed forces could not have procured entirely for itself). As usual the problem here is a lack of a (quantitative) sense of proportion. It is perfectly plausible that various Western actors share some moral responsibility for the mass murder. It is completely implausible that Suharto wasn't the main moral agent involved.

Unhelpful International Aid

This intellectual laziness also undermines Western actors' efforts to help. First the central cause of world poverty has been rendered invisible. What the poorest parts of the world all have in common is not an excess of exploitative Western capitalism but terrible governments. This is not a problem that can be solved from outside, for example by giving more money.

The central dilemma of foreign aid according to the Nobel prize-winning economist, Angus Deaton:

When the “conditions for development” are present, aid is not required. When local conditions are hostile to development, aid is not useful, and it will do harm if it perpetuates those conditions.

The conditions Deaton is concerned about are the local political institutions. If a country's rulers put in place pro-growth, pro-poor policies and institutions (like security, rule of law, economic freedoms, and good public education) then commercial interests will see the potential returns on investing and will do so. So no development aid will be needed. In contrast, if a country's rulers maintain institutions designed to extract as much economic value as possible from their people then no commercial interests will invest. But then aid won't work either. At best it will be swallowed up by the kleptocratic machine; at worst it will make it easier for the rulers to stay in power without responding to the needs of their people. In any case, it won't do any good.

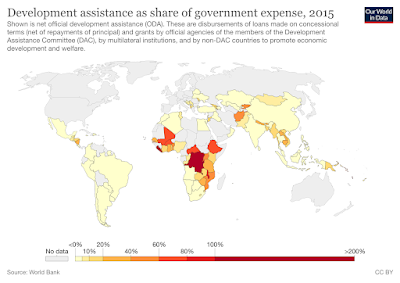

|

| In many poor countries international donors fund a large part of government budgets. Total aid spending can be higher than total government spending. |

Second, one might suppose that the superior economic power of Western actors should at least give them the power to extort institutional reforms by local rulers. This has been extensively tried but it doesn't ever seem to work. On the one hand, local political actors are very reluctant to make changes that would reduce the rents they can extract from the economy for the benefit of the 'public good'. So they make promises they have no intention of fulfilling. On the other hand, Western aid agencies rarely enforce the conditions, for various reasons including that domestic popular opinion blames them for any failures of aid to reach the poor. Again, the moral agency asymmetry misleads us into underestimating the power of non-Western actors to pursue their own interests and to resist doing what Western actors want.

Third, there is the attempt to work around local institutions by funding projects directly. Here the moral agency asymmetry strikes again by supporting a 'white saviour complex' approach to international aid (especially among charitable NGOs) in which activities organised by Western actors are assumed to be more effective than anything locals could do. These days such organisations are very concerned with measuring their effectiveness at converting donations into positive outcomes such as increases in literacy or reduced malaria mortality. But one thing they still don't do is think about their effects on the local political economy.

Besides funding corruption, undermining government incentives to be responsive to people's needs, and soaking up vast amounts of scarce government time on coordination issues, there is also the straightforward opportunity cost of aid programmes. Aid agencies tend to be well-funded in comparison to local government and civil society institutions. Therefore they can hire highly qualified people away from the jobs they would otherwise be doing (so e.g. PhDs in economics work for them - hopefully not just as translators - rather than the central bank). This is an example of Western (economic) power in action. But the effectiveness of the charities comes at the invisible cost of a loss of effectiveness of key local institutions. Ironically then the activities of aid agencies may help make it true that local institutions are incapable of responding to their people's needs.

Conclusion

We must drop the assumption that Western actors have moral agency and non-Western political actors do not. Western actors are not all-powerful. Supposing so leads to excessive optimism about what they can achieve to solve the problems of poor parts of the world, and then excessive disappointment and blame when they fail. Non-western countries have a story of their own, and it is often a complicated one with heroes and villains. We should pay attention to what kind we are dealing with, and try to use our limited influence to encourage the former and deter the latter. Above all we should recognise that it is local political actors who determine how people's lives go and who should be held responsible for that.